Some of Australia’s most daring architectural designs may still be dreams on a drawing board, if not for Peter Slattery’s pioneering approach to cost planning.

An astute businessman who built one of Australia’s most successful quantity surveying firms, Slattery died, aged 77, on 9 January 2022. During his long career, Slattery provided strategic advice on some of Australia’s most experimental and eye-catching public buildings, including the Melbourne Recital Centre and the Australian National Museum in Canberra. He also cost-managed ground-breaking projects like RMIT’s Storey Hall and Building 8, to name a few.

All buildings require a budget. Slattery, as an advocate of architecture and a skilled technician, challenged the traditional role of the quantity surveyor. He transformed the task of cost estimation from finding savings to uncovering new value. In doing so, he helped to elevate his profession, champion the role of architecture in the life of a city, and reshape the streetscape of Melbourne.

As architect and long-time friend Ian McDougall reflects: “Peter was in a league of his own. He not only had an intuition for estimating. He had a powerful instinct for the cultural impact and significance of the work.”

Born in Ivanhoe in 1944, Slattery completed his education at St Joseph’s Christian Brothers in Abbotsford, before joining Casey Byrne & Associates in 1962 as a first-year cadet. After completing his diploma in quantity surveying at RMIT, Slattery rapidly rose through the ranks of several firms before striding out on his own in 1976.

Slattery had what long-time colleague Steve Higginbottom calls a “basic instinct” for cost estimation. “He knew whether a project would stack up just from seeing the site. But he also had a talent for building real rapport with people. He had an honesty and forthrightness that commanded respect.”

From those early days, Slattery expanded the scope of the quantity surveyor beyond cost counting. He pushed boundaries by questioning funding models, procurement processes and structural designs. But most importantly, he showed institutions and governments how they could relate to the people they serve through good design.

As Slattery’s reputation grew, he used his influence to champion rising stars of the architecture world. Ian McDougall, the M in acclaimed architecture firm ARM, shared a space on the same floor of Slattery’s first office at 10 Peel Street in Collingwood and remembers his enthusiasm for emerging designers. “He was a mentor to many experimental and courageous young architects, and his innate understanding of risk – or lack of risk – meant architects could achieve interesting designs.”

Among those designs is ARM’s iconic Storey Hall. Inspired by an amethyst geode, the building’s RMIT jewel-like façade and whimsical ‘green brain’ crown set the university’s precinct apart from the rest of Melbourne. Another RMIT project, Edmond and Corrigan’s Building 8 on Swanston Street, presented a colourful, almost chaotic front that was in stark contrast to its monochromatic neighbours. Buildings like these, all the better for Slattery’s skilled cost planning, have put RMIT on the map as a university of modern architecture and design. Even more, they have inspired other universities and government agencies to adopt a new type of architecture.

Slattery was the architect’s ally. “Peter was known as the best QS in the business,” says Kerstin Thompson, the principal of Kerstin Thompson Architects, or KTA. “The role of the quantity surveyor is often associated with number crunchers, bean counters or penny-pinchers. And then there was Peter. He was a ‘larger than life’ character, full of joy and enthusiasm, who transformed the task of finding value with his professional generosity and personal warmth.”

Slattery understood and articulated value in new ways, and this trait helped KTA to develop its dynamic and award-winning approach to residential design. “It was never just about the bottom line with Peter. He challenged the notion that a quantity surveyor’s role was to say ‘no’,” Thompson adds.

Callum Fraser, director of skyscraper specialists Elenberg Fraser, agrees. “When I was studying at RMIT, I remember the Vice Chancellor saying that one figure – Peter Slattery – had been central to the university understanding its value proposition in a new way. Walking through a city can be a generic event because commercial developers see risk everywhere. But Peter created a space for architecture to redefine value. It was an amazing achievement.”

Slattery was as passionate about people as he was the built form. His support was a “vote of confidence” to many young architects, and his Christmas parties were the hottest ticket in town for any rising starchitect. He was just as committed to championing his profession and the people who upheld its values. His contribution to the Victorian Chapter of the Australian Institute of Quantity Surveyors spanned well over a decade and culminated in his appointment as president from 1996 to 1998. “He was, in the best possible way, an impatient man. He was keen to get things done,” remembers Gary Crutchley, Director of Wilde and Woollard, who was Slattery’s vice president and succeeded him in the role.

With his characteristic commitment to people, Slattery understood that AIQS was an “institute of individual members, not firms,” Crutchley observes. He encouraged young people to sign on as members, expanded the number of professional development and social committees and was a zealous promoter of the profession with government. “He played an instrumental part in the cultural change that transformed the Institute from an older-era club to a contemporary association.”

Slattery was curious about people and their stories, and this inclusive approach was good for business. As a young female architect in a male-dominated field, Kerstin Thompson remembers feeling “trepidation” at the prospect of working with someone of Slattery’s standing. “But Peter was respectful from day one, extremely encouraging and treated me as a peer.”

Slattery’s charisma belied the traditional values of cost estimation. He was a mountain of a man who dominated the room. He had a fiery temper but was also quick to chuckle. As Steve Higginbottom says: “Working with Peter was like living under a volcano. It was rich and enlivening with the occasional dangerous moment.”

Slattery was not perfect and his mistakes could be, in the words of his family, “Shakespearean” or “colossal” but also “endearing”. He loved exploring ideas – whether that was around the dining room or boardroom table. His six children remember a man who “always wanted to learn new things, take on challenges, change his opinions, begin new chapters”.

He was a practised raconteur who enjoyed a good story and a glass of red wine, and this would open another chapter and leave another legacy. After handing the baton of his quantity surveying firm to two of his six children, Josh and Sarah, in 2000, Slattery and wife Cate purchased Terindah Estate on the Bellarine Peninsula as a property with potential. With the same characteristic combination of dreaming and doing, Slattery planted grapes, opened a restaurant, cellar door and function centre, created a destination for glampers and newly-weds, and collected several gold medals for his wine. In 2016 Halliday’s named Terindah Estate the “Dark Horse of the Year”.

Always a man on a mission, Slattery found new avenues for his proficient advocacy. He was president of the Geelong Winegrowers Association from 2004 to 2006, and after joining the board of Bellarine Tourism in 2008, held the position of chair for two years from 2012 to 2014. With that instinct for value, Slattery steered the amalgamation of the Geelong Winegrowers Association with its marketing arm Wine Geelong, strengthening the association’s financial position and expanding its reach. Roger Grant, Executive Director of Tourism Greater Geelong at the time, notes that Slattery “always understood the importance of the visitor economy and invested his energy and dollars into its growth.”

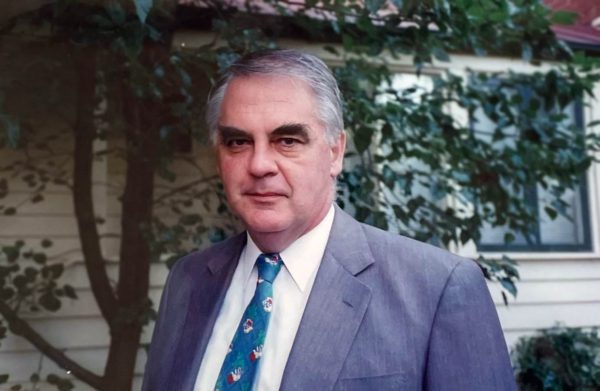

Every person who crossed Slattery’s path recalls a memorable encounter – whether that’s his red Ferrari or newest Citroen, finely tailored suits and ties or big smile. Slattery was more a phenomenon than a single person. Aside from his physical size and enormous mental capacity, Slattery was able to transform his ideas about the built environment into a practice that endures today.

“Peter helped Melbourne, as a city, to take its architects seriously,” says Callum Fraser. “It doesn’t seem like something that a cost planner should do. But he did. A lot of architects are rightly grateful for Peter’s influence on Melbourne’s built environment. But everyone who lives in the city should share this gratitude.”

Peter Slattery leaves behind Cate, his wife of 53 years, his six children Rachel, Sarah, Josh, Ruth, Hannah and Miriam, and his 17 grandchildren. But Slattery’s spirit lives on in his practice, which continues to embody the ideas and values he championed with passion and purpose for more than 45 years